New Guidance for Management of Biological Foodborne Outbreaks, and Identification of CCPs

The 52nd session of the Codex Committee on Food Hygiene (CCFH), chaired by the USA, was held virtually early March 2022. CCFH52 finalized its work on (a) a new Guidance for the Management of Biological Foodborne Outbreaks and (b) on a decision-tree to guide food business operators and countries in the identification of critical control points (CCPs) as part of HACCP plans (step 7 of 12) and as an essential component of the application of the Codex Alimentarius General Principles of Food Hygiene. Other topics were discussed with different degrees of detail and remain outstanding, i.e., on (a) the draft Guidelines for the Control of Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia Coli (STEC) and (b) the draft Guidelines for the use and reuse of water, and will be further elaborated through in-between electronic groups by the time CCFH53 might meet in person in San Diego, USA, no later than coming November 2022.

By Christophe Leprêtre (Keller and Heckman LLP)[1]

As per the on-going temporary procedural arrangements, the 52nd CCFH was virtual with an agenda limited to pending matters (e.g., no formal decision on new work). The meeting was overall attended by 106 Member countries, one Member Organization (i.e., the EU27), 22 Observer Organizations as well as Palestine.

Guidance for the Management of Biological Foodborne Outbreaks

• Main points of discussion

The guidance document aims at reinforcing the preparedness of food safety control authorities to manage national and cross-border foodborne disease outbreaks, in addition to existing applicable Codex guidelines setting principles for microbiological risk analysis.[2] It emphasizes the need for enhanced coordination between the human health network (i.e., medical doctors identifying foodborne illnesses in patients) and the food safety and veterinary network (i.e., running upstream to identify the source(s) of an outbreak and ensuring downstream risk management measures, i.e., food recalls, and further appropriate communication/warnings within the supply chain, and eventually to the public).

The guidance document put an emphasis on local and national networks interaction and rapid activations of exchange of information at the international level through the WHO network (INFOSAN) or its African equivalent (African Food Safety Alert Network, AFoSAN).

The guidelines emphasized the importance of rapid risk assessment and protocols which should be supported by the readiness of templates and standardized tools, such as (a) for collecting, maintaining and reporting updated information describing the outbreak – descriptive epidemiology; (b) arc-reflex questionnaire(s) (e.g., food-focused consumption questionnaires) to list hypotheses about the source and pathogen; (c) cohort and case-control questionnaires, (d) centralized online database helps in coordination efforts to identify potential sources and downstream spread; (e) template(s) for reporting on the outbreak and the outcome of investigations; and (f) template for requesting a rapid risk assessment; the two latter being included as examples.

Contaminated lots may be considered as separate from a production batch (and hence reduce the possible size of the food recalls). The definition of a lot is unchanged (and in some cases it may match that of a production batch).

The guidance document includes its own definition[3] of ‘risk communication’ (in addition to that of the Codex procedural manual[4]), as being valid in the context of these guidelines and not contradicting each other.

The guidance document specifies the importance of all types of “food contact surfaces” to encompass all materials that may come in contact with food, including equipment, packaging and containers and that those should not lead to any cross-contamination with foodborne pathogens or other risks.

On risk communication aspects, the text was amended to recommend establishing procedures for the identification of rumours and false information, noting the role of social media in this regard and that failure to try and address such rumours could lead to negative consequences, in particular during large outbreaks of foodborne pathogens, including viruses, as well as their toxins, where science-based rapid decisions are the only ones able to avoid serious illnesses and deaths.

The guidelines also contain a specific set of recommendations about methods of identification and sequencing of a foodborne pathogen to map it and allow rapid tracking (e.g., traditional such as pathogen isolation or polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based methods) as well as specific recommendations when using more advanced genetic methods such as whole genome sequencing method (WGS) and other molecular methods[5]. WGS is useful when isolates are highly related, and thereby enhances the ability of identifying the source of an outbreak with a high degree of accuracy when used in conjunction with epidemiological data. All methods are the basis for surveillance and monitoring, which are essential for early-detecting and investigating any outbreak.

• Main outcome

The text is going to be approved by the next Codex alimentarius Commission meeting (CAC45) as a final self-standing international norm, mid-December 2022.

New Decision-Tree on CCP identification as part of HACCP plans

• Main points of discussion

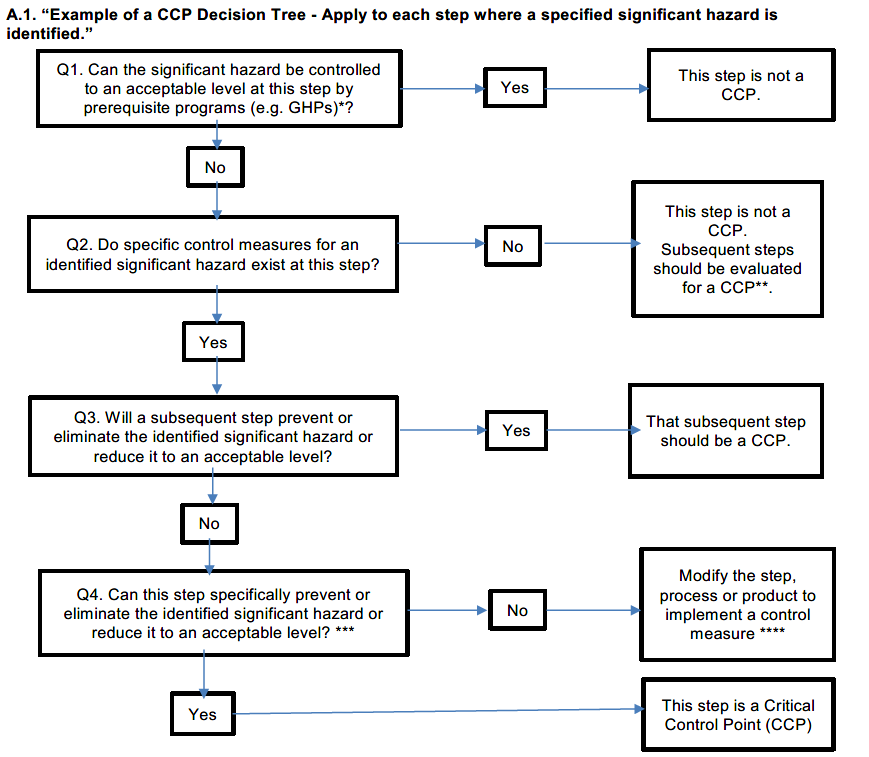

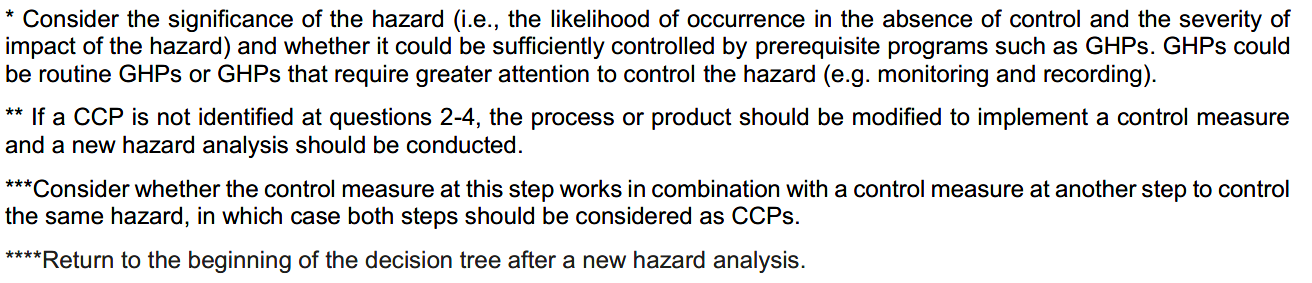

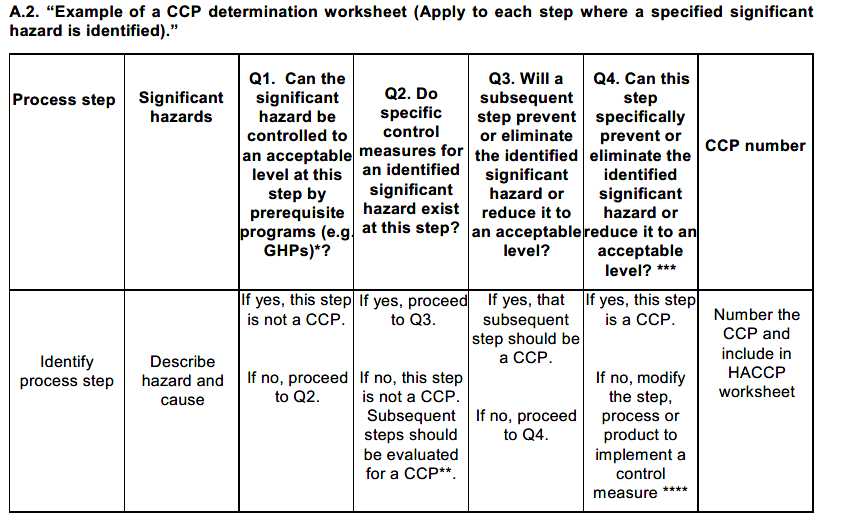

CCFH52 completed its work in developing a decision-tree to provide guidance to food business operators for the application of Step 7 of their HACCP analysis (out of 12 steps). During the discussion, it was noted, and this is important, that even in the presence of a significant (biological - or even chemical) hazard, it does not automatically mean that it requires a CCP to be put in place, but rather that it needs an extra attention to address it, whether it be by a GHP and/or a CCP. Several footnotes have been added to clarify the stepwise approach in the CCP identification/qualification. Figure 1 and Figure 2 show a snapshot of the final examples, as agreed by CCFH52.

• Main outcome

The text is going to be approved by the next Codex alimentarius Commission meeting (CAC45) mid-December 2022, as an appendix to the core Codex alimentarius Recommenced Code of Good Practice on Food Hygiene (CXG 1, 2022 version (current version: 2020)), with a reference to those charts added to Section 3.7 of CXG1. They are meant to be used as examples, not serve as such for ‘standardization’ purposes.

Figure 1. Example of Decision-Tree for Step 7 of HACCP Principle 2 - Determination of Critical Control Points (CCPs)

Figure 2. Example of a CCP determination worksheet (Apply to each step where a specified significant hazard is identified)

Guidelines for the Control of Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia Coli (STEC) in Several Raw or Unprocessed Foods[6]

• Main points of discussion

The proposed draft text was discussed during a pre-CCFH52 specific working group on the basis of an inter-CCFH session electronic working group advancing the recommendations in the guidelines while taking into account the scientific inputs received from the Joint FAO/WHO risk assessment body on microbiological risks, JEMRA, in 2020 on raw beef and raw milk and in 2021 on leafy vegetables and sprouts. It was noted that microgreens were also intended to be covered by the scope of the future guidelines (possibly covered by the term ‘sprouts’). A revised definition of indicator microorganisms was added[7]. A reference to ‘risk modelling tools’ has been added to stress their usefulness for control measures on the prevention reduction or elimination of the hazard but also their limitations, including the need for quantitative data, which should be clearly specified and understood by the risk managers. CCFH52 also agreed on a definition of ‘Raw milk’ as a “milk[8] that is intended for direct consumption or a primary input for dairy products and which has not been heated beyond 40ºC or undergone any treatment that has an equivalent effect”.

• Main outcome

CCFH52 agreed to task a new electronic Working Group (EWG)[9] to continue working on the various parts of the guidelines, including the development of specific annex on sprouts describing interventions relevant to control of STEC. JEMRA work will be taken into account, as well as all the materials discussed at CCFH52. A pre-CCFH53 ‘physical’ Working Group (PWG) will review the report of the EWG and prepare further the text for CCFH53 plenary decisions.

Guidelines for the Safe Use and Re-Use of Water in Food Production

• Main points of discussion

One main issue was the consideration of the reference to “potable water” or to “drinking water”. At this stage, CCFH52 recognized “potable water” as the most acceptable way forward. Regarding the 30 paragraph-long section covering reused water in fresh fruits and vegetables, they have been retained so far, but it was recognized that specific cross-check with other existing text[10] may lead to a simplification of these guidelines. CCFH52 heard different views on the addition of examples and decision-trees as an appendix or replaced with references to the relevant national/local guidance but agreed to retain them for now and consult JEMRA. CCFH53 will consider how appropriately they may be included in the document (content and location). On the third key issue relating to whether JEMRA or FAO & WHO could be asked to validate examples, it was clarified that they may provide recommendations - through a critical review of such examples - on how they could be adapted, if possible, in countries with water scarcity and/or limited resources without putting food safety at stake. CCFH52 reviewed briefly the annexes of fishery products and dairy products but it agreed to defer technical discussions to the EWG.

• Main outcome

CCFH52 agreed to send back the further drafting of these guidelines on Water reuse to a new EWG, chaired by Honduras and co-chaired by Chile and the EU as well its annexes on fresh produce, fishery products and dairy sector. The EWG co-Chairs and FAO & WHO are requested to have regular communications to facilitate consideration of the JEMRA outputs and get advice on any relevant issues in the document (e.g., critical review of examples, examples of decision-support systems currently included in the document, recommendations on how to adapt examples to countries including those with water scarcity and/or limited resources, examples of specific risk mitigation strategies, etc.). CCFH53 will based its decisions on further recommendations from a Working Group meeting in person (PWG), considering the report from the EWG and additional comments.

Other Business and Future Work

The Codex Secretariat is to issue a Circular Letter to request submissions for new work proposals. The willingness of Japan with help of New Zealand, and of Canada with the help of the Netherlands to prepare discussion papers on possible revisions of existing Codex texts respectively on the control of pathogenic Vibrio species in seafood and on Viruses in foods was noted.

JEMRA was requested to collate all relevant scientific information on Salmonella and Campylobacter in chicken meat in preparation for an update of the existing Guidelines for the Control of Campylobacter and Salmonella in Chicken Meat (CXG 78, 2011 version) and recalled their support for JEMRA to develop a full « farm-to-table » risk assessment for Listeria monocytogenes in (all) foods to inform any future update of the Guidelines on the Application of General Principles of Food Hygiene to the Control of Listeria monocytogenes in Foods (CXG 61, 2009 version). As per customary practice, each proposal for new work should clearly identify needs for scientific advice. The Observer GAIN suggested to develop a new work on “food safety in traditional markets”.

A dedicated working group on « CCFH Work Priorities », chaired by the USA, will be held in conjunction with CCFH53, to consider proposals for new work and prioritize them.

---

CCFH52 report is to be accessible at http://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/meetings/en/

All CCFH52 working documents are available at https://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/meetings/detail/en/?meeting=CCFH&session=52

This article was first published in the World Food Regulation Review April 2022 Issue Vol. 31, Number 11.

[1] Food Safety Specialist, i.e., Senior Regulatory and Scientific Affairs Counselor at Keller and Heckman LLP Brussels office.

[2] Codex Alimentarius Principles and Guidelines on: (a) Working Principles for the Risk Analysis for Food Safety for Application by Governments (CXG 62, 2007 version), (b) Exchange of Information in Food Safety Emergency Situations (CXG 19, 2016 version), (c) Conduct of Microbiological Risk Assessment (CXG-30, 2014 version), (d) Conduct of Microbiological Risk Management (CXG 63, 2008 version) (d) National Food Control Systems (CXG 82, 2013 version).

[3] “The exchange of information on the biological risk among stakeholders (e.g., government, academia, industry, public, mass media and international organizations)”

[4] “The interactive exchange of information and opinions throughout the risk analysis process concerning risk, risk-related factors and risk perceptions, among risk assessors, risk managers, consumers, industry, the academic community and other interested parties, including the explanation of risk assessment findings and the basis of risk management decisions.”

[5] Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE); Ribotyping, multiple-locus variable-number tandem-repeat analysis (MLVA), etc.

[6] Raw beef, fresh leafy vegetables, raw milk and raw milk cheeses, and sprouts.

[7] “microorganisms used as an indicator of quality, process efficacy, or hygienic status of food, water, or the environment, commonly used to suggest conditions that would allow the presence or the proliferation of pathogens, a failure in process hygiene or the process. Examples of indicator microorganisms include counts of total mesophilic aerobic bacteria, coliforms or faecal coliforms, E. coli and Enterobacteriaceae.”

[8] As defined in the Codex General Standard for the Use of Dairy Terms (CXS 206, 1999 version).

[9] Chaired by Chile and co-chaired by France, New Zealand and the United States of America.

[10] Code of Hygienic Practice for Fresh Fruits and Vegetables (CXG 53, 2017 version).